Medical Research Category

Dr. Abdoulaye Djimdé (Republic of Mali)

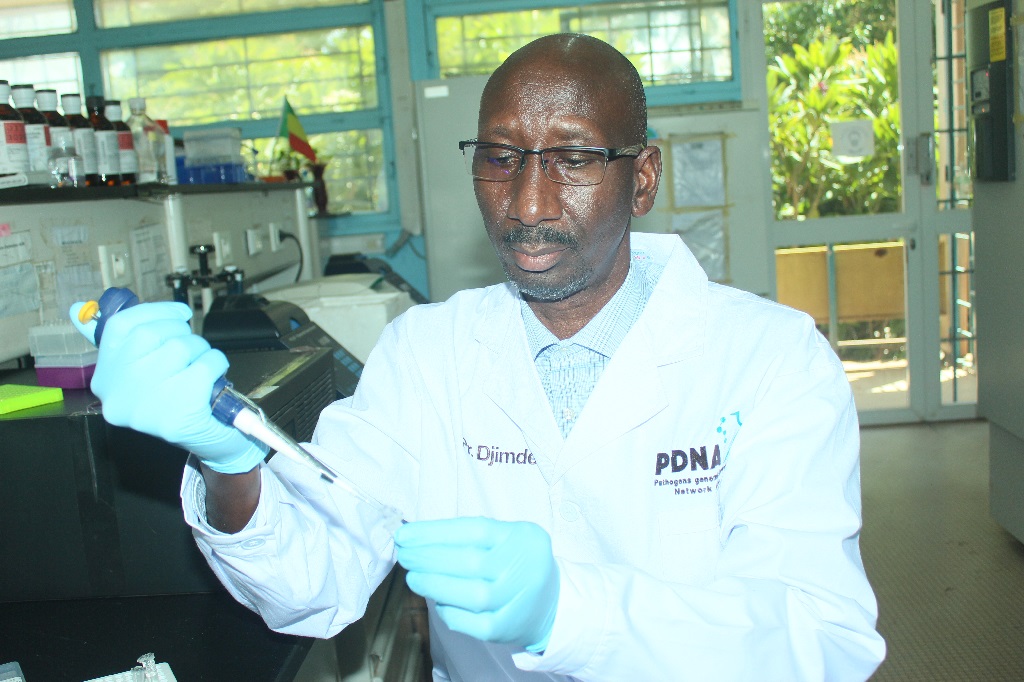

Born in the Republic of Mali in 1964. 61 years old. Researcher specialized in molecular parasitology. Obtained Pharmacy Doctorate at the National School of Medicine and Pharmacy Bamako, Mali and Philosophy Doctorate at the University of Maryland, USA. Current Director, Parasites & Microbes Research & Training Center (PMRTC), University of Science, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako. (Photo credit: Abdoulaye Djimdé)

Born in the Republic of Mali in 1964. 61 years old. Researcher specialized in molecular parasitology. Obtained Pharmacy Doctorate at the National School of Medicine and Pharmacy Bamako, Mali and Philosophy Doctorate at the University of Maryland, USA. Current Director, Parasites & Microbes Research & Training Center (PMRTC), University of Science, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako. (Photo credit: Abdoulaye Djimdé)

Reasons for Award

The tragic experience of losing a sibling to malaria as a child and his initial career as a young pharmacist motivated Dr. Djimdé to pursue research on malaria, an endemic disease threatening the lives of people in Africa. The results of his research over the past thirty years have contributed significantly to improved treatment and control of malaria and have had an important impact on the health policies of African governments and the WHO. In particular, Dr. Djimdé, together with collaborators, had shown that the Plasmodium falciparum gene that conferred chloroquine resistance in laboratory strains was responsible for chloroquine-resistant malaria in malaria patients through his field research in malaria-endemic areas of Mali. He went on to design molecular markers that can confirm chloroquine resistance in the field. He also demonstrated the safety and efficacy of antimalarial drugs through clinical trials of artemisinin-based combination therapies. Furthermore, he established the Pathogens genomic Diversity Network Africa (PDNA), a collaborative research network for malaria control among 12 African countries (currently 16 countries) and built a system for sharing experimental protocols and genetic data. In addition, as director of the Parasites & Microbes Research & Training Center (PMRTC) at the University of Science, Techniques and Technologies of Bamako, he has worked diligently to train young scientists and has collaborated with many international research groups. By doing so– despite diverse challenging conditions– he has developed the center into a central hub of an international network of malaria research. Through these accomplishments, his research has saved the lives of many people living in malaria-endemic areas, and he remains firmly committed to realizing the dream of a “malaria-free Africa.”

Summary of Achievements

Despite recent progress, malaria remains one of the most pressing public health problems in sub-Saharan Africa. Growing up in rural Mali, Dr. Abdoulaye Djimdé had a firsthand tragic experience with this terrible disease, which took the life of one of his beloved brothers, when he was just 12 years of age. This experience moved him to become an anti-malarial scientist later in life and prevent other children from dying of malaria. In pursuit of this goal, he undertook pharmacy studies in Mali and graduated with honors. Working as a young pharmacist, he was used to send a box full of antimalarial drugs including pills and injectables each year to his father who remained in the village with the rest of the family. In keeping with the African tradition of sharing the little one had, receiving these medications ensured prompt treatment of malaria cases within Djimdé’s family, extended family and friends, and the neighborhood. He quickly realized that, if his malaria actions were to reach beyond his community back home, he needed to do more. So, he volunteered his time at the Malaria Research and Training Centre at the National School of Medicine and Pharmacy in Bamako and later enrolled as a PhD student in microbiology and immunology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

The main highlights of Dr. Djimdé’s 30-year career are as follows.

1. Developing a molecular marker of chloroquine resistance

Chloroquine was a very effective treatment for malaria, and was also both safe and inexpensive, so it was used as an anti-malaria drug in areas across the world for many years. However, in the second half of the 1950s, Plasmodium falciparum, which gives rise to the worst, fatal symptoms among the malaria-causing protozoans that infect humans, gained resistance to chloroquine. The Pfcrt gene that causes chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum was later identified, but because strains cultivated in labs were used for this research, it was not known whether Pfcrt was actually the causative gene of chloroquine resistance on the ground in areas with malaria epidemics in Mali. Together with his collaborators, Dr. Djimdé is the first to show that Pfcrt is the gene responsible for chloroquine resistance, even in endemic sites and designed a reliable molecular marker for chloroquine resistance in the field. His assay system was adopted first in sub-Saharan Africa, and later around the world. Under his leadership, the research team used that molecular marker to prove that chloroquine resistance was widespread in Mali, which led to a change in the first-choice treatment for malaria in the country.

2. Clinical development of antimalarial drugs

When Plasmodium falciparum, which had become resistant to chloroquine, was reported around the world, it became necessary to clinically introduce new, more effective antimalarial drugs. Dr. Djimdé and his fellow researchers carried out Phase II to IV clinical trials of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT) and verified their safety and effectiveness in sub-Saharan Africa. Artesunate-pyronaridine (PyramaxR), one of these ACT, had been registered as a malaria treatment drug 10 years earlier in Europe, but due to concerns about its safety its use was limited to one treatment per patient. However, in sub-Saharan Africa, children were infected with malaria multiple times each year. Effectiveness could not be expected with this administration of PyramaxR. Dr. Djimdé and his team carried out careful long-term cross-cutting research on a large scale, gathering 13,350 cases of malaria and treating them with one of four ACT, including PyramaxR, then following each case over two years. The outcomes showed that artesunate-pyronaridine was effective even when repeatedly administered to patients with consecutive episodes of malaria, and that there were no safety issues with multiple administration. This discovery led the WHO to approve multiple uses of PyramaxR. After this, PyramaxR came to be used in 27 countries, including 22 in sub-Saharan Africa, and has saved the lives of many African children.

3. Genetic diversity of African Plasmodia

Dr. Djimdé convinced his fellow researchers in 12 African countries to establish the Plasmodium Diversity Network Africa (now the Pathogens genetic Diversity Network Africa (PDNA)), and designed a system to easily share experimental protocols, samples, genetic data, and more. Joint research carried out through this network led to the first genetic research into malaria-causing protozoans across Africa, and Dr. Djimdé and his colleagues discovered the existence of major subpopulations of P.falciparum in sub-Saharan Africa. This research contributed to the WHO’s decision to update its policy on malaria, which was previously not-country-specific, but rather handled in the same way in sub-Saharan Africa by taking a method suited to that country based on each country’s local data. Dr. Djimdé and his PDNA colleagues are continuing to work together to assess the potential impact of Plasmodium genetic diversity in response to malaria interventions, antimalarial drug resistance, vaccine effectiveness, and control of vector organisms.

4. Training young researchers through research

Dr. Djimdé is focused on creating a variety of programs to build research capacity in Africa and has spearheaded the formation of global strategic partnerships investigating malaria and drug resistance in the African region. Notably, as the founding director of Developing Excellence in Leadership and Genomics Training for Malaria Elimination (DELGEME) a training program he runs with his PDNA colleagues, he is committed to training excellent young researchers – for example, he has developed a wide-ranging training program on genetic and bioinformatics, including those of malaria-causing protozoans and human hosts, for young scientists from 17 sub-Saharan African countries. The young researchers who studied in DELGEME have produced numerous excellent research outcomes in the fields of genomics and bioinformatics. Recently, the program has been expanded into DELGEME Plus and is also stressing research into anti-microbial drug resistance under Dr. Djimdé ’s leadership.

Dr. Djimdé conducting research on Malaria in the laboratory of the Parasites & Microbes Research & Training Center (PMRTC).

(Photo credit:Abdoulaye Djimdé )

Dr. Djimdé trains young researchers from African countries at Pathogens genomic diversity network africa (PDNA) laboratories in Bamako

(Photo credit:Abdoulaye Djimdé )

Dr. Djimdé listens to communities to realize his dream of a malaria-free Africa.

(Photo credit:Abdoulaye Djimdé )